Flatten airports in X-Plane

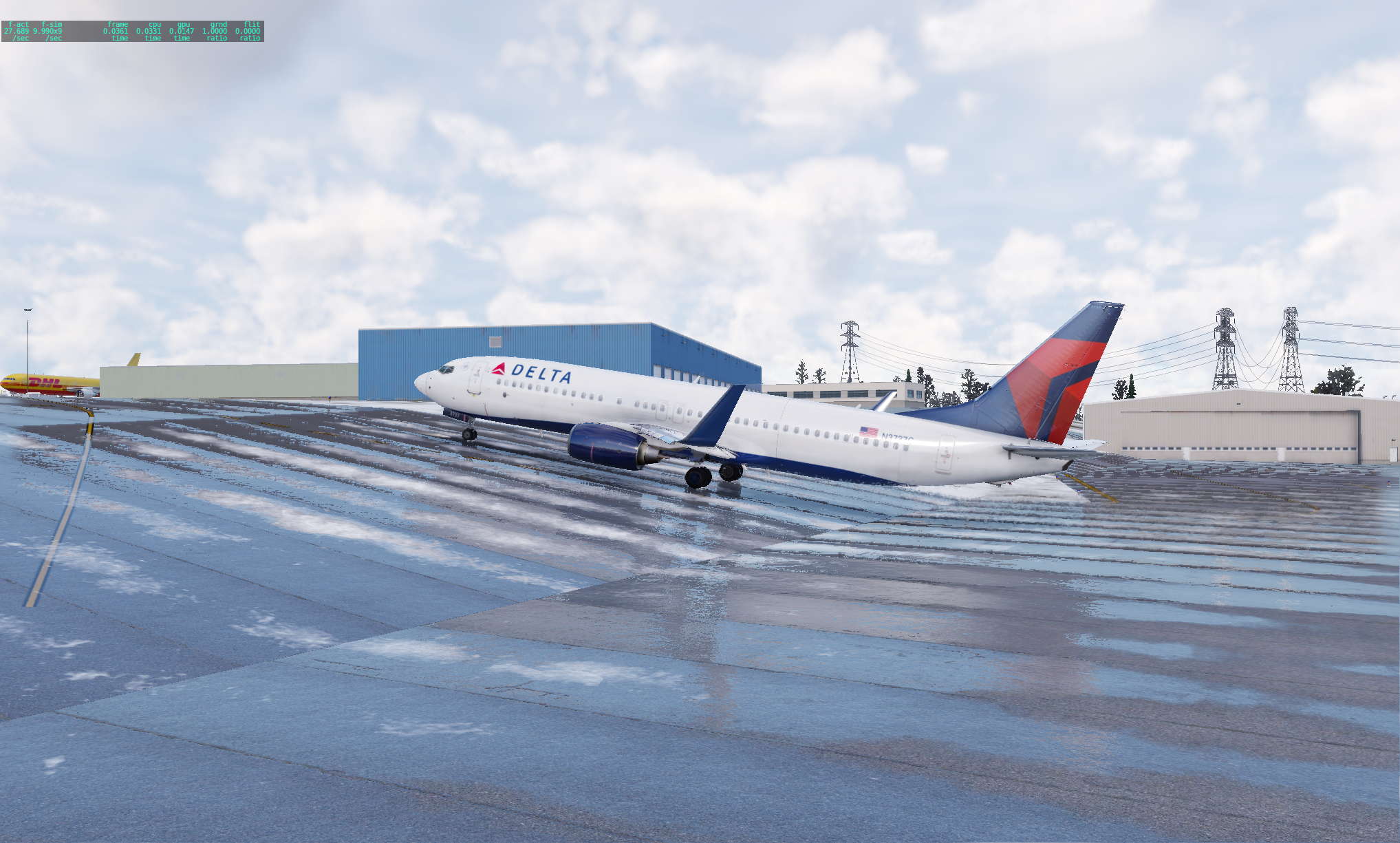

Some airports in X-Plane have terrain issues that can be quite entertaining.

This Delta 737-800 got lost in the maze of cargo ramps at PANC and was trying to taxi back to the terminal when it encountered a steep icy taxiway. It required 65% N1 just to get up the slope.

Clearly a fix is required. It turns out to be quite simple. In the global airports file apt.dat, find the offending airport. In this case, it’s PANC where its entry looks like:

1 149 0 0 PANC Ted Stevens Anchorage Intl

1302 city Anchorage

1302 country USA United States

1302 datum_lat 61.174155556

1302 datum_lon -149.998188889

1302 faa_code ANC

1302 gui_label 3D

1302 iata_code ANC

1302 icao_code PANC

1302 region_code PA

1302 state Alaska

1302 transition_alt 18000

...To flatten the airport terrain, add the line 1302 flatten 1 after the airport header, so that the block now looks like:

1 149 0 0 PANC Ted Stevens Anchorage Intl

1302 flatten 1

1302 city Anchorage

1302 country USA United States

1302 datum_lat 61.174155556

1302 datum_lon -149.998188889

1302 faa_code ANC

1302 gui_label 3D

1302 iata_code ANC

1302 icao_code PANC

1302 region_code PA

1302 state Alaska

1302 transition_alt 18000

...But what about when X-Plane is updated; the global airport apt.dat file gets overwritten. My workaround is to apply the fix programmatically after update:

#!/bin/bash

APTDAT="/Users/$(whoami)/X-Plane 12/Global Scenery/\

Global Airports/Earth nav data/apt.dat"

perl -pi -e '$_ .= qq(1302 flatten 1\n) if /PANC\sTed.+/' "$APTDAT"I suppose, I could create a custom airport directory for the airports that I flatten, but then I’d lose out on any future modificationsto those airports that Laminar Research publishes in its updates. I’ll have to think about that one.