A deep dive into my Anki language learning: Part I (Overview and philosophy)

Although I’ve been writing about Anki for years, it’s been in bits and pieces. Solving little problems. Creating efficiencies. But I realized that I’ve never taken a top-down approach to my Anki language learning system. So consider the post the launch of that overdue effort.

Caveats

A few caveats at the outset:

- I’m not a professional language tutor or pedagogue of any sort really. Much of what I’ve developed, I’ve done through trial-and-error, some intuition, and a some reading on relevant topics.

- People learn differently and have different goals. This series will be exclusively focused on language-learning. There are similarities between this type of learning and the memorization of bare facts. But there are important differences, too.

- As I get further and further into the details, more and more of what I discuss will be macOS specific. I’m not particularly opinionated about operating systems. And my preference has more to do with the accumulated weight of what I’m accustomed to and as a consequence, the potential pain of switching. In the sections that deal with macOS specific solutions, feel free to skip over that content or read it with a view toward thinking about parallel tools on whatever OS you are using.

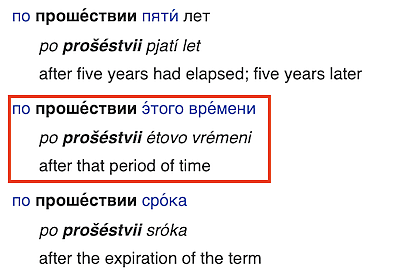

- I use Anki almost exclusively for Russian language acquisition and practice. Of necessity, some particularities of the language are going to dictate the specific issues that you need to solve for. For example, if verbs of motion aren’t part of the grammar of your target language (TL) then rather than getting lost in those weeds, think about what unique counterparts your TL does have and how you might adopt the approaches I’m presenting.

We that out of the way, let’s dive in!