Why is the U.S. obsessed with home ownership?

If you’ve lived in the U.S. for any length of time, you realize that we have a national obsession with home ownership. Yet I’m beginning to wonder about this bit of American orthodoxy. I’ve owned 4 homes and none of them seemed like much of an investment to me. The last home that we sold was an enormous loss. We are now in a transition, anticipating our new move; so we are house-free (and debt-free!) So it’s an ideal time to unpack the complexities of home ownership.

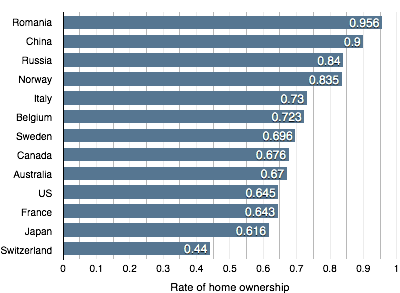

Rates of home ownership worldwide are not uniform; and these rates are not associated with most measures of individual and collective financial success. For example, the highest rate of home ownership is found in Romania, a country not known for its economic productivity. And the lowest rate of home ownership is among the Swiss, a people known for the financial-savvy.1 In fact, the Swiss save almost 17% of their disposable income compared to about 5% in the United States. If we construct a relationship between per capita GDP and the rate of home ownership for the countries listed in the chart above, the linear correlation coefficient is 0.3112. In other words, there isn’t a relationship between home ownership and economic productivity.

In the U.S., the Federal bias is toward home ownership is both longstanding and questionable. Presumably, the Federal government has in interest in promoting asset accumulation among its citizens. But as Edward Glaeser has pointed out2 one wonders why homes, among all the other forms of assets should be favored in this way. Hypothetically, the Fed could provide individuals with similar magnitude tax deduction for the purchase of stock. Since one of the most prominent ways that the Federal government subsidizes home ownership is through its mortgage interest deduction, the question of whether the mortgage interest deduction actually aids in asset accumulation is legitimate. Among the problems with the hypothetical connection between the mortgage interest deduction and wealth accumulation are:

- The mortgage interest deduction disproportionately benefits wealth Americans. Analyses have shown that the relationship between household income and the tax savings from the mortgage interest deduction is non-linear.

- The mortgage interest deduction encourages people to buy larger houses In an effort to take a larger deduction, people take out larger mortgages to pay for larger houses. There are important environmental and other reasons to discourage this trend.

Aside from the theoretical side, there are real economic findings that suggest home ownership may be an inefficient investment. From 1890 to 2005, when adjusted for inflation, home prices rose 103%, much lower than the rate of rise of the stock market. Since 1900, the U.S. stock market returned approximately 10% per year - about an order of magnitude more than home ownership. Yale economics professor Robert Shiller estimates that the ROI for U.S. home ownership is between 0 - 1%. As others have noted, 1% maintenance costs would mean an ROI of under 1%, perhaps even negative. Many other factors can lower this value further - including real estate transaction costs, property taxes, and homeowners association dues.

I’ve come to regard some of Americans’ love affair with home ownership as an anachronism. In the generation before mine, no one lived in HOA’s. People tended to work at the same job for their entire adult lives. And they tended to change houses much less often. All of these factors have changed in the ensuing generations. Yet the informal analyses that prospective buyers do are partly based on assumptions that derive from the “old days.”

In Canada, the analysis is simpler. Apart from buying leverage, there is no advantage to taking out a mortgage because there is no mortgage interest deduction.

Our housing plan

Our plan is based on the following considerations:

-

We will live below our means. I grew up in a family of 4 in an 1100 square foot home. We did fine. Massive swaths of granite, Cambria, and designer fixtures are for suckers. BMW’s, Mercedes, Land Rovers, and other “clown cars” are for suckers.3 Lawns onto which people pour toxic chemicals and on which people waste millions of gallons of fresh water are for show. We are committed to leaving below our means.

-

We will decouple housing from employment. Houses are massive anchors. We encountered that when we were on the verge of building a massive house. Fortunately we recovered from our delusion. Here’s the deal. Obligations reduce the range of choices open to the obligor; and houses are enormous obligations. By living below our means, we will reduce the burden of our obligations and become independent enough to think about work on its own merit rather than according to the degree to which it allows to live in a certain house.

-

We will eliminate or minimize our mortgage. We are saving the overwhelming majority of our household income with a goal of paying cash for our next house. If a desirable house that fits our well-defined functional needs comes along before enough cash has accumulated, we will take out a mortgage for no more than $150,000 - one that we can easily pay off in 5 years or so.

-

We will be patient, slow, and deliberate. We’ve made bad real estate decisions. Our last house was massively over-priced. We failed to read the imminent bursting of the U.S. housing bubble. We failed to consider how nettlesome and expensive HOA’s are.4 After selling our last house and living in a rental home, I’ve begun to realize just how easy it is to make more rational decisions by staying out of the market until everything is just right.

See also

- Owning a Home Isn’t Always a Virture: NY Times

- The Historical Rate of Return for the Stock Market Since 1900

- History Says Home Real Estate is a Bad Investment

- A Chart to Put the Canadian Housing Bubble in Perspective

- Canadian Housing’s Chilly Future, Part 1

- Canadian Housing’s Chilly Future, Part 2

-

The story of homeownership in Switzerland is complex. The Swiss don’t actually prefer to rent. A 1996 survey revealed that 83% of Swiss would prefer to own their homes rather than rent. source. It turns out that Swiss tax policy makes home ownership very difficult because of imputed rent. Swiss home owners are taxed on an imputed income as if they had rented their home to another individual. Fortunately, such a scheme was deemed unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court back in 1934. Helvering, Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Independent Life Insurance Co. ↩︎

-

Glaeser, Edward L. 2011. Rethinking the Federal Bias Toward Homeownership. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research 13(2): 5-37. Link ↩︎

-

In the interest of accurate disclosure, we were once suckers according to this standard. We’ve recovered; and the prognosis is good. ↩︎

-

Our last home was part of a HOA. The rules were irregularly enforced and there were simply not enough homes to support the ongoing maintenance costs. The cost of maintaining (and eventually replacing) the private paved road was a “ticking time bomb.” ↩︎