An approach to interleaved and variable musical practice: Tools and techniques

“How do you get to Carnegie Hall” goes the old joke. “Practice, practice, practice.” But of course there’s no other way. If the science of talent development has taught us anything over the last fifty years, it’s that there is no substitute for strategic practice. Some even argue that innate musical abilities don’t exist. Whether it’s nature, nurture, or both, show me a top-notch musician and I’ll show you a person who has learned to practice well. Here we’ll take a dive into a set of practice techniques that I’ve developed, along with tools to realize them in the practice room.

Table of contents

The cornerstone: deliberate practice

Let’s get the most important thing about practice out of the way first.

If you’re not practicing deliberately, you’re wasting time. It’s not that you won’t improve, but it will take you much longer to get there. The late Anders Ericsson, the researcher who coined the term “deliberate practice” distinguished between three approaches to practice. In order of effectiveness, they are:

- Naive practice - This is be one step beyond just noodling on your instrument. There’s no goal, written or otherwise. Maybe you’re just playing through your pieces but not repeating anything that needs more attention.

- Purposeful practice - If you have goals and use your practice sessions to work toward them, addressing weaknesses systematically, you’re probably practicing purposefully and you will definitely improve.

- Deliberate practice - A step beyond purposeful practice lies deliberate practice, differing mainly in intensity and structure. Ericsson defined several distinguishing characteristics of deliberate practice:

Characteristics of deliberate practice

| Characteristic | Attributes |

|---|---|

| Specific and well-defined goals | Setting clear and specific goals that focus on improving specific aspects of performance. These goals are often broken down into smaller, achievable sub-goals. |

| Focus on improvement | Purposeful and designed to improve performance. It involves identifying weaknesses or areas for improvement and engaging in activities that target those specific areas. |

| Repetition and repetition with refinement | Requires substantial repetition of specific tasks or skills. However, it goes beyond mindless repetition by incorporating feedback, analysis, and refinement of each repetition to achieve incremental improvements. |

| Mental effort and full engagement | Demands significant mental effort and concentration. It requires intense focus and engagement, pushing individuals beyond their comfort zones and challenging them to continually strive for improvement. |

| Expert guidance and feedback | Working with a knowledgeable coach, mentor, or teacher who can provide expert guidance, feedback, and instruction. This external feedback helps individuals identify areas for improvement and make necessary adjustments. |

| Systematic and structured approach | Follows a systematic and structured approach. It involves breaking down complex skills or tasks into smaller components, practicing each component separately, and gradually integrating them into a coherent whole. |

| Continuous monitoring and self-assessment | Ongoing monitoring and self-assessment of performance. Individuals actively seek feedback, evaluate their progress, and make necessary adjustments to optimize their learning and development. |

| Challenging and working outside the comfort zone | Pushes oneself to operate at the edge of their current abilities. It involves tackling tasks that are slightly beyond their current skill level, which creates a state of “optimal discomfort” and fosters continuous growth. |

| Time and effort commitment | Requires a considerable investment of time and effort. It is not a casual or sporadic activity but rather a regular and dedicated commitment to focused practice over an extended period. |

| Adaptability and flexibility | Practice is adaptable and flexible. It allows individuals to modify their approach, strategies, and techniques based on feedback and new insights, constantly adapting to improve performance. |

Three approaches to deliberate practice

With that framework in mind, it’s helpful to consider three ways of approaching a passage.

Blocked practice

In blocked practice, you work on a section with repetitions until you arrive at a particular goal - tempo, tone quality, etc. On reaching that goal, you move on to the next section. After running your list of sections, you’re done. Studies show that blocked practice results in effective learning; but with a major caveat. Practitioners of blocked practice don’t retain the ability they acquired as effectively as practitioners of other approaches.

Variable practice

Variable practice involves frequent and creative changes of technique. Play it slowly, then fast. Then with dotted rhythms. Reverse the dotted rhythms. It turns out that retention and mastery of the material are much better with variable practice than with straight blocked practice.

Interleaved practice

In interleaved practice, we weave repetitions of a given passage throughout the practice session. You practice that section, go on to some other section, then return to the first passage.

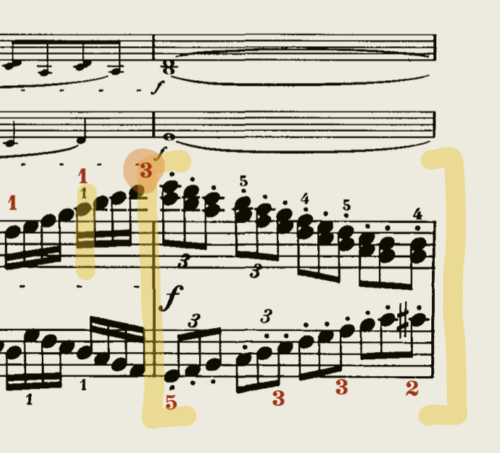

One of the most productive things you can do in practice is to find the difficulties, block them off, bracket them and focus your attention on those sections. Here’s a typical bracket:

The descending thirds in the right hand needs work to get them up to tempo. But a little later down the road, there’s a similar section with a scale in sixths. There’s another bracket. Eventually, we can conceive of the piece as a collection of bracketed sections that are stitched together by easier material. This is the setup for interleaved practice, where we practice the first section, then the second, and onward before looping back to the first section. Like variable practice, it turns out that this technique is also more effective for long-term skill retention than blocked practice.

Combining variable and interleaved practice for maximum effect

What if we were to combine variable and interleaved practice by changing up the practice techniques for each section as we loop through them? Something like this:

| Section | Technique |

|---|---|

| A | slow, deliberate tempo |

| B | dotted rhythms, moderate tempo |

| C | practice in blocks of four 16th notes |

| A | reverse dotted rhythms |

| B | staccato |

| C | fast-slow alternating |

The idea is to continually vary the technique between sections and over multiple “cycles” also focusing, of course, on the specific weaknesses that need to be addressed section-by-section. Does this combined variable and interleaved practice work? Empirically, I would say “yes”; but if it has been subjected to actual study, I don’t know. I can only say that it keeps me focused and constantly moving through the sections of the music in a way that addresses the technical difficulties.

How I do it

When approaching a piece that I’m learning, by the time that I’m ready to actively practice it, I will have already gone through the score carefully, bracketing sections that need more intense work. Typically I will have given these sections alphabetic designators A, B, C and so forth. In one practice block, I will choose three sections for interleaving and variable. Then I’ll practice them like this:

| Section | Technique | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| A | slow, right hand | 1 minute |

| B | dotted rhythms | 1 minute |

| C | reversed dotted rhythms | 1 minute |

| A | slow, left hand | 1 minute |

| B | reversed dotted rhythms | 1 minute |

| C | dotted rhythms | 1 minute |

| A | very slow, hands together | 1 minute |

| B | legato | 1 minute |

| C | staccato | 1 minute |

| A | hands together, a little faster | 1 minute |

| B | slow tempo, as written | 1 minute |

| C | legato | 1 minute |

Of course, this can go on for many cycles - I’ve shown only four here. And the duration could be different. If the sections were long, then you may want more than one minute. My one invariable here is that I always do these cycles in groups of three. It’s an arbitrary choice; but it feels like if I did any less than three, then there’s not much interleaving and it’s closer to the less-effective blocked practice. But if I do cycles of more than three, I feel like I’ve already lost some of the gains by the time a section comes up again. But this is how a practice bout goes for me:

- Run a cycle of the first three practice brackets. This takes about 14-20 minutes depending on how long I’ve allocated to the sections.

- Move on to the next three sections and repeat.

All of this is aided by some tools that free me from having to watch the clock or set individual timers.

Tools to help combined variable and interleaved practice

Seconds Pro

Although this can be done with pencil and paper, I’ve discovered that it’s more efficient to use an application to support this kind of practice. Specifically, Seconds Pro. I have no affiliation with the developer; and I don’t recall how I stumbled on the idea of using it. It’s clearly aimed at the physical exercise training crowd.

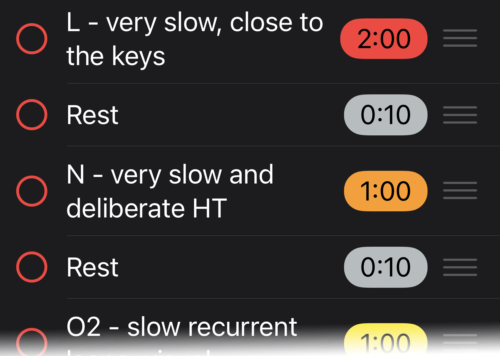

The basic principle of this app is to perform an activity for a predetermined period of time, then move on to another activity, then another, and so on. In the variable/interleaved practice approach, this is what we want to do. Practice section A for 2 minutes with slow tempo, then section B for 2 minutes with dotted rhythms, etc. Seconds Pro allows you to set up these protocols in advance. When it’s time to practice, press the play button and it advances automatically through the routine. Here’s an example of one of my routines:

These routines can have as many steps as you wish. Consistent with the variably-interleaved approach, sections L, N and O2 above reappear several times as this routine unfolds, each time practiced in a different way.

There are two notable features in my practice routines that I would like to point out:

Rests

This kind of high-paced, high-turnover practice can be physically stressful. That’s why I place rests strategically between blocks. With particularly challenging blocks, I program longer rests. The rests give me a moment to shift the music to a different page and gives me time to relax the hands and mentally prepare for the next section.

Repurposing the Cadence feature as a metronome

As mentioned, Seconds Pro is intended as a physical workout tool. Since certain workouts (like cycling) are often done at a particular cadence, there is a field in each action to include a numerical cadence. The idea is that you time your pedal stroke to the programmed cadence. It should also work just like a metronome; so if your practice task has to be done at a particular tempo, you can add the MM value in the Cadence field of the action.

MultiTimer

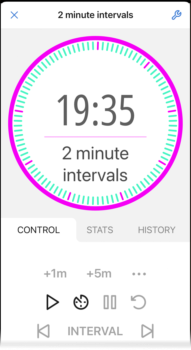

If you don’t want to go to the trouble of setting up an entire routine in Seconds Pro, then you can do something similar in another iOS app called MultiTier: Multiple timers. Like Seconds Pro, it works off the principle of interval timers, but doesn’t require you to script an entire routine. This can be helpful if you’ve put together a handwritten practice plan in your practice journal and just want help with the timing.

The selling point of MultiTimer is that you can set up multiple interval timers and save them for generic re-use. For example, I have interval timers that provide cycles of 1 minutes of “on” time and 5 seconds of rest. Another timer provides 2 minute work cycles separated by 10 seconds of rest. You can also program the number of cycles in each timer. If I’m using the 1 minute cycle timer, I will practice the first spot for one minute, take 5 seconds rest, then move on to the next spot. Visual and audible signals in the app tell the user when it’s time to move on.

When I’m using MultiTimer, typically I will designate three practice spots at a time; so the number of repetitions that I program in each cycle is always a multiple of 3.

It may sound daunting to have to program this; but it’s actually quite easy. The process of creating an interval timer in the app is intuitive and nearly self-explanatory. But if I have a chance I’ll post a short video about how to set it up.

Before closing, I should mention the other tool that aids in this type of deliberate practice is an 12.9" iPad Pro running forScore. The ability to non-destructively bracket and annotate sections for practice is invaluable. I can leave marks that I would not necessarily want in my permanent paper score, annotations that are only relevant to practice and not to performance.

Conclusions

If you’re going to practice, practice purposefully (or better yet, deliberately, a difference mainly in intensity) - meaning you have goals in mind and your minute-to-minute approaches to practice are all designed to achieve those goals. There are three broad types of practice depending on how you cycle through the material - blocked practice, interleaved practice, and variable practice. Interleaved practice, where you practice one section for a while, move on to another section, then eventually return to the first section is known to be more effective than blocked practice. In variable practice, you practice the same passage in different ways or with a different focus. Variable practice has also been studied and found to be effective. The approach I describe here combines the interleaved and variable practice. Two app-based tools Seconds Pro and MultiTimer can help pace you through this kind of practice.

Happy practicing!